Carroll Dunham: Green Period. Prints, Drawings, and Paintings, 2018-2022

JRP Editions

Edited by Dan Nadel

Authors: Carroll Dunham, Dan Nadel, Mary Simpson

English

September 2023

ISBN: 978-3-03764-608-3

Hardcover, 305 x 242 mm Pages: 136

Pictures: Color: 115

︎ Order the book

JRP Editions

Edited by Dan Nadel

Authors: Carroll Dunham, Dan Nadel, Mary Simpson

English

September 2023

ISBN: 978-3-03764-608-3

Hardcover, 305 x 242 mm Pages: 136

Pictures: Color: 115

︎ Order the book

Theatrum Anitomicum, 1610, Engraving by Willem Swanenburgh from a drawing of the Leiden anatomical theater by Jan Cornelis Woudanus

I Saw It and Didn’t See It

There’s a story I heard once that haunts me every time I enter a medical environment. A mother described giving birth via C-section. As the doctor cut into her abdomen, she screamed, “I feel that!” and he replied, “No, you don’t. You just think you do.”

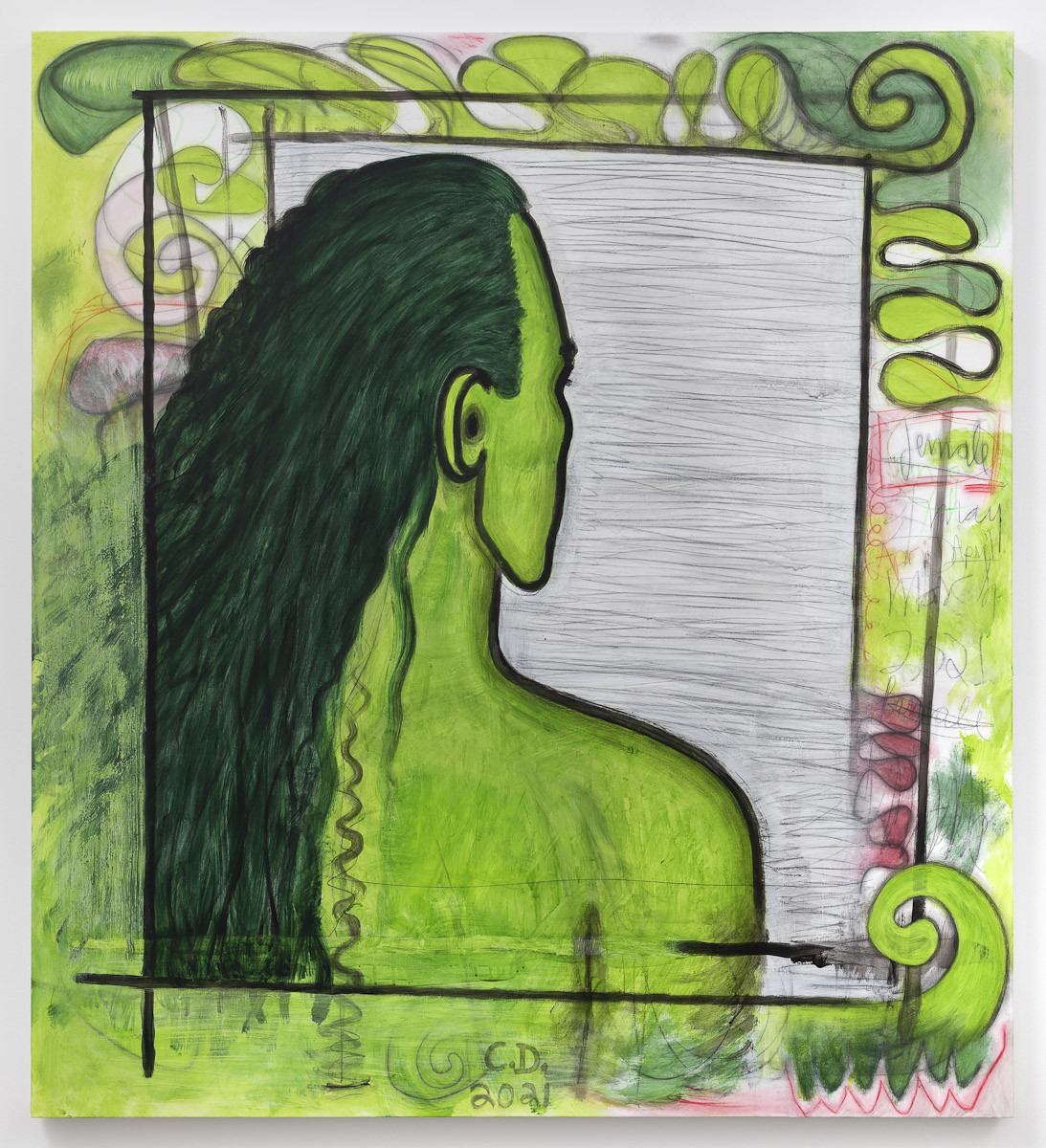

Carroll Dunham, with Green Period., has created a fantasy of observation. It begins with a speculative device, the qualiascope, imagined by the (real) neuroscientist Giulio Tononi as an instrument for detecting consciousness. In Dunham’s fantasy, this invention coincides with the appearance on Earth of a group of green beings, who immediately become the subjects of study for a privileged class of humans. After capturing some of these green beings, the humans use their qualiascope to study the creatures’ physical forms, sexual habits, and sense perceptions.

To some eyes, the provocation of Dunham’s new body of work might be its focus on sex and genitalia. For decades, people have said Dunham makes dirty pictures. Yet for decades his works—many of which depict nipples, penises, scrotums, pubic hair, and anuses—have been endowed with such playful inertia they sidestep sex appeal entirely. (As one critic wrote, nipples in a Dunham painting look like little Puritan hats).(i) Why would hairy vulvas make a painting seem dirty? Because they’re difficult?

Melissa Febos once wrote of the rules we make around difficult things: “We like to assign the trouble we have to the thing that troubles us. The problem is not that vagina is an unsexy word. Or that nipples never do look like pencil erasers. The problem is that we have exiled sex in our minds. We have isolated it from the larger inclusive narrative, and we have limited its definition to that which serves the most privileged class of protagonists.”(ii)

Dunham has painted unsexy penises and vulvas—and nipples that sometimes look like pencil erasers—for many years, and his figures are from a class that is decidedly unprivileged. Beginning in 2008 with his Bathers series and continuing to this most recent body of work, the protagonists in his paintings are, as he says, “pre- or post-technological.”(iii) Their origin lies outside of contemporary culture: they are either thousands of years old or dropped from outer space, or perhaps teleported from an ancient future. Buck naked, human-ish, with male and female anatomy, they are bathing, hunting, frolicking, and fighting in forests, pools, and deserted landscapes. And yet, despite some critics’ porn fixation, there is one thing his figures have never done (before now): have sex.

A friend referred to the figures in the new works as “lovers,” and I had to correct him with the decidedly unerotic term “mating couples.” For there is nothing to suggest romance here, unless you’re someone who observes a sexual encounter between two praying mantises in a bell jar, complete with decapitation, and creepily describes the scene as “making love.”

The action in Dunham’s recent works is exactly as cold as their clinical titles imply. In the Coitus Diagrams, for example, the figures look down or away, bracing themselves against each other’s rigid bodies. Dunham has shown us sex, yet the works are not about desire. Or, to phrase it another way, if sex is about desire, Carroll Dunham’s paintings are not about sex.

In some images, the figures’ sex organs are framed in close-up like microscopic slides. The drawn and painted frames also imply imprisonment, as in Qualiascope: Female & Male Captured Together. Several paintings show the male figure’s arms cleanly amputated, like pruned tree limbs, the spiral marks on the stumps making direct reference to Dunham’s Trees paintings (2007–12). In other works, both figures’ appendages spread past the edges of the canvas, calling us to imagine what lies beyond the enclosure.

Carroll Dunham, Qualiascope: Coitus Diagrams (Three), 2020-2021

Carroll Dunham, Qualiascope: Coitus Diagrams (Three), 2020-2021Urethane, acrylic, crayon and pencil on linen, 70 x 60 inches

Carroll Dunham, Qualiascope: Female Taken Alone, 2021

Urethane, acrylic, crayon and pencil on linen, 51 x 46 inches

As I look at these works, I find I’m less provoked by the sex the figures are having than in the placement of myself as a viewer. While Dunham’s context is science, his subtext is power. What lies beyond the enclosure is us.

Giulio Tononi’s qualiascope specifically tracks subjective experience, measuring qualities, as Dunham puts it, like “the redness of red or the sweetness of honey.”(iv) A small step brings us from sweetness and red to the experience that for centuries has been the test for consciousness itself: the painfulness of pain. It’s ancient, the idea that pain can’t be felt by animals, or infants, or indigenous people, or Black women, or anyone other than the privileged class inflicting it. And it persists today, as much in the hospital as in the slaughterhouse.

The conventions of surgical theater are as old as surgery itself. In Ancient Greece, operations took place in spaces built for public observation—literal theaters—and this language has never left us. Doctors still “perform” surgery, the body positioned as a mere prop. (For millennia, surgery was also performed with no anesthetic. As the story that opened this essay shows, that practice hasn’t left us either.) With Green Period., Dunham has placed his protagonists on this stage, and we, the viewers, are seated in the audience, watching the mundane exposure of their bodies.

To witness a staged event is to be complicit with that event, whether an exhibition or vivisection. Here begins an attempt to answer why it is important to see ourselves in a painting. When an artist makes us look at an image from the perspective of a scientific observer, with all the power that role implies, the artist is showing us our complicity in a structure that keeps others othered. To show us the part we play in it. To show us ourselves.

_______

*The title of this essay is from a line of dialogue in an Ursula K. Le Guin novel which imagines a human race violently enslaving the green and human-like indigenous inhabitants of a newly encountered planet. Ursula K. Le Guin, The Word for World is Forest [1972], Tor Books, New York 2010, p. 37.

1. Sanford Schwartz, “A Bosch for Us Now,” The New York Review of Books, November 8, 2018, p. 12.

2. Melissa Febos, “Mindfuck: Writing Better Sex,” The Sewanee Review, Summer 2020, https://thesewaneereview.com/articles/mind-fuck-writing-better-sex (last accessed April 2023).

3. Carroll Dunham, “Green Period.,” Green Period., JRP|Editions, Geneva 2023, p. 124.

4. Ibid., p. 126